Oregon market prices tease, but input costs higher

Published 5:00 am Wednesday, July 31, 2024

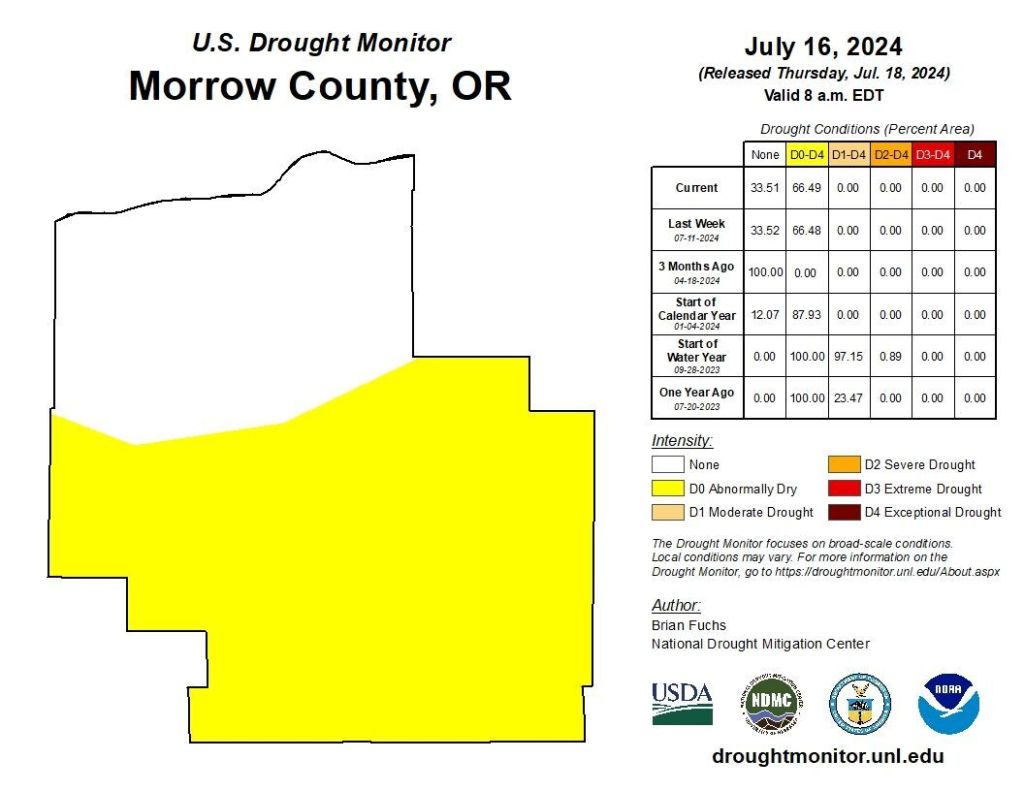

- 20240716_county41049_trd.jpg

PENDLETON — The agriculture outlook for Oregon is mixed, with strong prices for cattle but relatively low prices for wheat.

Trending

A winter wheat crop that looks to have good yields could partially offset the sluggish market.

Oregon State University Extension soil scientist Don Wysocki is encouraged by the appearance of this year’s winter wheat crop.

“We’ve had good spring rains so there’s a little bit of water under this unless it turns really hot, dry and windy,” Wysocki said. “Now it’s going to dry a little slower. We’re probably going to be just a few days later than we normally would be, but if you can predict the weather, then I can tell you.”

Trending

Wysocki said rains in May and June have pushed the crop expectations well above average with expected good quality as well.

Rainfall in May at the Eastern Oregon Regional Airport in Pendleton was 2.62 inches, more than double the long-term average of 1.21 inches.

June rainfall at the airport totaled 0.51 inches, below the average of 0.94 inches.

Wysocki said wheat prices will be about $5.60 a bushel, “so that’s not a very good price.”

The reason, he said, is a slower export market, which is where most of Oregon’s wheat is sold.

Jason Middleton, Pacific Northwest regional manager for United Grain, buys much of the locally grown wheat, so he is well-tuned to the market process.

“We’ve been around the world and back because there’s a lot going on,” Middleton said. “The grain business in Oregon, Washington and Idaho is very focused on export, as opposed to the Midwest, but ever since COVID, everything’s been out of whack.”

Russia is a big exporter now, he said, and has sold a lot of wheat at low prices.

“Anybody who will buy it has effectively put a lid on rallies out of the U.S.,” Middleton said. “Since the last time we talked, my bid got as high as $6.40 delivered to McNary, which is where I post my bid, and McNary’s roughly 60 cents off a pound from Portland.”

The elevation and barge freight to Portland costs about 60 cents extra a bushel, he said.

Middleton said $4.85 a bushel was a recent low before that.

Russia has crop problems

Middleton also said Russia seems to be struggling from a wheat production perspective. The country had some winter kill issues, so the Russian crop could be down in the low 18 million tons, which is a small crop for them now.

“They were willing to buy lesser-quality wheat out of the Black Sea, so we lost a lot of demand that way,” Middleton said. “They’re not going to have the volume they were able to force on the market so hopefully they will come back to the U.S. in some fashion.”

He said it pains him to blame things on the pandemic, “but inputs, fertilizer and chemicals farmers need to use every year to grow wheat, went through the roof. It got really expensive to grow wheat, potatoes, onions, you name it.”

Production costs also are skyrocketing for Oregon cattle producers, although market prices “are really at an all-time high,” said Matt McElligott, a Baker County rancher and president of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association.

He pointed to the increased cost of fuel and labor as well as the price of renting grazing land.

McElligott said another stress on ranchers financially and emotionally, as well as on their cattle herds, is the proliferation of wolves.

“Our pregnancy rates go down when predation goes up,” McElligott said, “and the cost is borne by the producer. There are compensation programs through the state but they don’t even come close to covering the costs and you lose.”

In addition to livestock, he said, elk and deer populations have suffered from the presence of wolves, and “cows are becoming the next best thing for wolves to eat.”

Dogs not welcome in grazing land

McElligott said wolves have had another detrimental effect on cattle ranchers.

They’re finding it harder to use dogs to work cattle “because cattle don’t like dogs anymore since they’ve been exposed to wolves.”

The cattle market, however, gives ranchers reason for optimism.

“The main summer video sales are going to start in a couple weeks and that will be a real telltale sign,” McElligott said.

He said cattlemen are getting a bad rap on greenhouse gases, but emissions of greenhouse gases from cattle is only 2-2.6% of global emissions, compared to 26% for transportation. He said this campaign is driven “by anti-animal agriculture people that want to see nobody raise a chicken, nobody raise a cow, and nobody raise a sheep.”

Water supplies

It might be easier to get agriculture commodities to market than to get water to producers, according to J.R. Cook, founder and director of the Northeast Oregon Water Association.

“There is a water management problem by the state of Oregon that we have been trying to address for a significant number of years,” Cook said. “The problem for farmers is we have a sustainability plan and a way to meet sustainability targets, but we keep getting new interpretations and new regulatory activities thrown at us without any public process or any chance for a science-based debate.”

Cook said the Umatilla Basin has four of the seven state-designated critical groundwater areas. The decline in groundwater started his career.

“We’ve been working on that for decades but we still have not fixed that,” he said. “We have the objectives adopted and we know where we need to go but we’re not getting there because there’s no accountability on the agencies that work with us to fix the problem in the region.”

Cook said agricultural producers are invested, as well as the tribes and cities, “but the regulatory agencies and the people who give them their budget every year aren’t committed or invested, so that’s where we have a major breakdown. We’re trying to figure out a pathway forward with the governor’s office and the Legislature to fix that breakdown.”